Indigenous Woman. While some Indigenous peoples faced discrimination both during and after the war, Clark-Jones recalled in a 2003 memoir that there was an atmosphere of camaraderie in the Armed Forces: “I never once felt any discrimination in the air force; it did not seem to matter that I was young, Aboriginal or a woman.… there was no time or place for discriminatory practices.”

A veteran of the Second World War, Clark-Jones joined the Aboriginal Veterans Society. She advocated for the fair treatment of Indigenous ex-service people. She was co-founder and first president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada. Clark-Jones devoted her life to seeking equality and greater power for women in Canada.

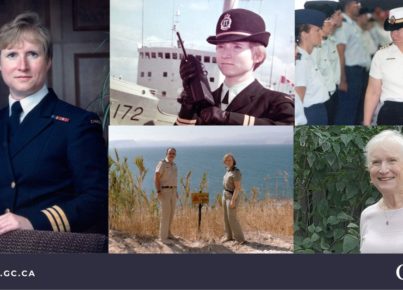

Fiercely patriotic, Bertha Clark-Jones joined the Royal Canadian Air Force at age 18 in 1940 (see also RCAF Women’s Division). After finishing her physical training course, Clark-Jones achieved the rank of corporal. And was put in charge of a squadron as drill instructor. She travelled the country in this role, working at various military bases. However, Clark-Jones remained disappointed in never having served overseas. After the war, she used her military experience to advocate for the fair treatment of Indigenous veterans and later joined the Aboriginal Veterans Society (see Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars).

While some Indigenous peoples faced discrimination both during and after the war, Clark-Jones recalled in a 2003 memoir that there was an atmosphere of camaraderie in the Armed Forces: “I never once felt any discrimination in the air force; it did not seem to matter that I was young, Aboriginal or a Indigenous woman.… there was no time or place for discriminatory practices.”

After leaving the air force, Bertha Clark-Jones intended to live close to her family. They were in the Paddle Prairie Métis Settlement in northern Alberta. While the Canadian government provided ex-service personnel loans to buy and farm land, as per the Veterans’ Land Act, Clark-Jones could not own land on the Métis settlement because she was a Indigenous woman.

Clark-Jones was also aware that “First Nations peoples lost their Status when they left the reserves to join up, and this in turn meant that they did not have any land or houses when they returned.” This was due to provision of the Indian Act, which specified that First Nations soldiers who were absent from their reserves for four years lost their Indian Status. Witnessing this level of discrimination launched Clark-Jones’s advocacy for human rights and Indigenous women’s rights. (continue reading)

You must be logged in to post a comment.